A new graphic novel, Zahra’s Paradise, is released that shows the long and ongoing struggle of Iranians for a better, safer and non-fundamentalist future. The New York Review of Books:

The people that Zahra and Hassan come across in their quest tell them stories: of missing relatives, confiscated property, executions, and the like. Hassan, for example, visits at his home a young man who shared a cell with Mehdi and others at Kahrizak Prison—the Tehran detention center where both male and female prisoners were allegedly assaulted and tortured during the 2009 protests. He describes these horrors: “I was raped! Raped in the name of their God, in the name of their Iran! Raped in the name of their prophet”¦It is their Islamic republic—not me—that is covered in filth!” Khalil’s drawings reconstruct this event as the young man is remembering them: his interrogators forcing him to face a cell wall; his trousers being pulled down; the document he was forced to sign afterwards, presumably saying he was well treated.

The novel’s drawings often reveal this kind of terrible irony. They represent a distinctly Iranian style of humor, a means of puncturing pretence and power. Iran’s leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, is depicted as the Caliph of an all-male harem, choosing a new favorite among the politicians and clerics who are vying for his attention. The Revolutionary Court is pictured as a Kafkaesque maze of stairs, running upside down and sideways and seemingly going nowhere. Iran’s judiciary is evoked by a huge, gaping set of a mullah’s jaws. Moving stairs and runways, carrying an endless line of the accused enter the jaws from one side; they emerge from the maws of the mullah, after side trips to the torture chamber and the confession room, carrying signs of their prison sentences: “10 years,” “2 years,” “17 years.”

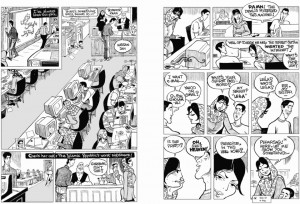

The protagonists of Zahra’s Paradise are in many ways representative types. Zahra is like the thousands of mothers who in Iran today persist in the search for missing sons and daughters and who courageously demonstrate before detention centers and in public parks, and issue open letters to the authorities seeking the freedom of their incarcerated children. Even today, a number of these mothers gather every Saturday in a Tehran park for this purpose, often risking arrest. This gathering is included in the book, and the police are shown dispersing the women. The brother, Hassan, provides an entrée into the world of Iran’s irreverent youth culture: into bedrooms plastered with posters, endless hours on the internet, intense camaraderie and the furtive but easy interaction between men and women in internet cafes. A taxi driver, taking Zahra and Hassan on their ronds, abandons his cab in the middle of Tehran’s perennially snarled traffic to fetch himself and his passengers a glass of his favorite watermelon juice. As the drawing appropriately shows, his absence hardly matters, since the traffic is not moving at all.